Could Egypt happen to Pakistan?

Could Egypt happen to Pakistan?

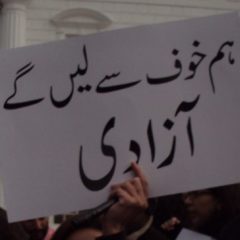

Since January 25, 2011, the world has been captivated by developments in Egypt. One after the other, like the domino effect, major cities in Egypt erupted in protests, calling for the removal of the Mubarak regime. Reminiscent of the color revolutions that took place in Eastern Europe during the twilight of President Bush’s administration, the Egyptian situation has caused consternation for a lot of international actors, and analysts are on the edges of their seats trying to determine what this sociopolitical movement means for democracy in the middle east, and for political rights in the modern Muslim world at large.

There are a lot of causal factors that point to the current turmoil in Egypt. Most believe that it was Hosni Mubarak’s elongated rule that will come to 30 years in power if he continues till October 2011. Almost all of this administration has been under emergency rule, which says a lot about the democratic process in Egypt and the freedoms Egyptian citizens enjoy – despite being allied to the United States. Even though Egypt has seen two revolutions – one in 1919 and another in 1952 which brought Gamal Abdel Nasser to power – the current regime is also descended from the ‘revolutionary’ legitimacy of the Nasser and Sadat eras. On January 21st, Ahmad Aggour wrote that Egyptians should learn a lesson from the Tunisians and send Mubarak packing, just like Zine el Abidine ben Ali.

It seems that the current revolution is designed to install a true democracy of the Egyptian people, thereby upturning the status quo established by the July 23 Revolution of 1952.

Larbi Sadiki has written an interesting opinion piece in Al Jazeera, where he labels the Egyptian and Tunisian revolutions as ‘bread intifadas’. Arguing that the real terror facing Muslim societies is that of political, social and economic marginalisation, Sadiki claims that these bread riots come and go but regimes stay. Countries like Egypt, Algeria and Tunisia continue to be “the fodder of chaos in the absence of social justice, culturally sensitive sustainable development and democratic mediating networks and civic channels of socio-political bargaining and inclusion”. “Oppositions and dissidents have not yet learned how to infiltrate governments and build strong political identities and power bases. This is one reason why the protests that produced ‘Velvet revolutions’ elsewhere seem to be absent in the Arab world.”

Sadiki says that bread uprisings have positive and negative outcomes: “On the positive side, they act as elections, as plebiscites on performance, as an airing of public anger, they issue verdicts on failed policies and send stress messages to rulers”.